“America’s El Greco” – 1984 & 2004 Sport Artist of the Year

Artist Biography | Style & Inspiration | Key Sport Works & World Influence

Barnes working on ‘Boxing’

No more appropriate contemporary artist than the late Ernie Barnes could have been honored twice as the first Sport Artist of the Year in 1984 and again in 2004 as the 20th Anniversary selection. The critically acclaimed Neo-Mannerist painter masterfully captured the passion and elegance of sport in his paintings throughout his impressive 43-year career. Barnes drew artistic inspiration from all facets of his complex life, from childhood through adulthood and his celebrated football career. No matter what his activity, all directions pointed to art as the core of his identity.

“Throughout my five seasons in the arena of professional football, I remained at the deepest level of my being—an artist.” ~ Ernie Barnes

Sunday’s Hero

Barnes’ 1995 autobiography, From Pads to Palette, shows him as an introspective artist and an eloquent writer. In the Forward, Jack Kemp, former San Diego Chargers quarterback and Ernie’s teammate, says:

“He has become a beacon of hope, shining from the inner-city streets and the dirt playgrounds of rural North Carolina… a manifestation of the American Dream… Ernie’s art helps play a very positive role in uplifting… our nation.”

Volleyball: 1984 Olympics

Ernest Eugene Barnes Jr. was born in Durham, North Carolina on July 15, 1938. The country was recovering from the depression, but war was looming in Europe. Race relations were unstable, and Jim Crow laws still mandated the segregation of blacks and whites. His father worked as a shipping clerk for Liggett Myers Tobacco Company. Ernest Barnes, Sr. would return from long, tiring days to his home on a dirt road in “the bottom,” a poor section of Durham, to play some Scott Joplin ragtime on the piano and then fall to sleep reading the paper. Ernie, his older half-brother, Benny Rogers, and his younger brother, James, passed the time drawing designs with sticks in the wet Carolina dirt. Their mother, Fannie Mae Geer, had bigger plans. She was determined to make possible education and cultural enrichment for her children.

Barnes’ mother initiated his exposure to world culture by taking Ernie to the house where she worked as a domestic to meet her employer, Frank Fuller Jr., a wealthy attorney. In Fuller’s study, Barnes was introduced to fine art. “I enjoyed this room of polished, mahogany walls with leather chairs, shelves of leather-bound books and the sound of classical music.” Fuller recognized Barnes’ affinity for art and would tell him “about the various schools of art, his favorite painters, the museums he visited and other things my mind couldn’t quite comprehend at the age of seven.” By the first grade, Barnes had been exposed to the masterpieces of Toulouse-Lautrec, Delacroix, Rubens, and Michelangelo.

Ring Around the Rosie

Barnes credits his mother not only with guiding him toward formal scholastic education but also with being the source of his internal psychological balance that gave him the scope to excel as an artist. Time and time again, Barnes names emotional insight as the key to artistic greatness.

“I am convinced that my sense of homecoming in the company of women dates back to my mother’s compassion and tenderness which transmitted to her children. Through the years of my pro career, I acquired a patina of hardness and brute strength. A certain callousness. But this always fell away in the easy ambience of women. They kept alive in me the one essential quality no artist can be without – sensitivity. Receptiveness not only to color and light, but to the underlying spiritual messages those elements convey… You must be able to receive those poignant insights before they can be expressed in art. It’s a basic to the creative life.”

Ernie Barnes, “ ~ From Pads to Palette”

High Aspirations

As a young boy, Barnes did not have an easy time with his sensitivity. He was overweight, mercilessly teased, and beaten by his classmates. Barnes turned to his sketch books for sanctuary. “When I was at home and drawing,” Barnes wrote, “I was happy… I made friends with lines.” At adolescence, he became interested in girls and realized that one of the best ways to gain their admiration was through athletics. Barnes signed up for the football team. He didn’t enjoy the physical violence of the sport, but his mother knew that it would help him advance in society and insisted that he continue.

Throughout his school days, Barnes often stole away by himself to draw in his sketchbook. His secret occupation was discovered by Mr. Tucker, the high school’s masonry shop teacher. Instead of reporting Barnes to the principal’s office, Tucker questioned him on his life goals. Tucker encouraged Barnes to begin weight training. Barnes followed Tucker’s program with devotion and, by his senior year, sweated his way to captain of the varsity football team and state champion in the shot-put. By graduation, Barnes had received 26 scholarship offers from colleges and universities. This outpouring was Barnes’ ticket to an education that otherwise he might not have been able to afford. None of these offers came from Duke University or from the University of North Carolina, both only miles from his home. Barnes graduated from Hillside High in 1956, well before anti-discrimination laws were widely enforced. The struggle for racial equality played a pivotal role in the forming of Barnes’ identity and in his development as an artist.

The Maestro

Barnes spent four years at the all-black North Carolina College, today known as North Carolina Central University, majoring in art. Aside from playing football, Barnes studied with chairman of the art department, Ed Wilson, and co-chairman, William B. Fletcher. Under these two artists, Barnes learned the fundamentals of drawing, painting, anatomy, structure, drapery, perspective, light and shade, sculpture, design, figure study and art history. Ed Wilson pushed Barnes to find himself in his art, to utilize his experiences and pay attention to what was going on around him. Barnes said that because of Wilson he “came to better understand the art process and the athletic process as being parts of one entity.” In search of psychological truths for the themes of his work, Barnes began transferring his visual and emotional experiences on the football field to his canvases. The power from this fusion of brute force and grace became the foundation for his greatest works.

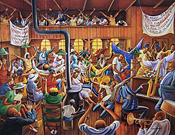

Solid Rock Congregation

While at North Carolina College, Barnes was able to visit the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh where he viewed the work of Rubens, Caravaggio and Van Gogh. After asking the museum tour guide “Where are the paintings by Negro artists?” and getting the response, “I’m afraid your people don’t express themselves this way,” Barnes came face to face with the adversity he would have to overcome as a black artist. Ed Wilson discounted the tour guide’s ignorance after the trip by showing Barnes and his classmates the works of black artists Henry O. Tanner, Edmonia Lewis, Duncanson, Archibald Motley, Hale Woodruff, Sargent Johnson, and Palmer Hayden. At that time, letters from professional football teams started pouring into his mailbox, and Barnes sold his first painting, “Slow Dance,” to Sam Jones of the Boston Celtics for $90.

At 21 years-old, Ernie Barnes was the tenth round draft choice for the Baltimore Colts. After being invited along with his college coach to see the Colts play the Giants in a championship game and to enjoy his first hotel experience, Barnes signed a $6,500 per year contract, with a $500 signing bonus. Based on his experience at the game, Barnes painted “The Bench,” which won him an interview with a news reporter whose article dubbed him “Ernie” Barnes. For the next five years Barnes played professional football for the San Diego Chargers and the Denver Broncos. Now a 6’3” 250-pound guard, he held his own on the football field. Even in uniform, he continued his art. Barnes kept a pencil in his sock to take notes in down time. His teammates called him “Big Rembrandt.” During his time with the Chargers, Barnes was commissioned to draw his teammates for the game programs. Barnes sketched during practices and meetings and was once fined by Denver head coach Jack Faulkner for sketching while watching game film.

“I have always analyzed myself strictly and strongly felt the need to feel centered; to feel self. Part of me was in search of its complimentary half, and the illusiveness of that anonymous being was causing me seriously to think about the legitimacy of my wasting more time playing football… I disliked the fact that I had been clinging to the game and to a weak team because I was driven to being good and I didn’t know how to stop proving that I was.” ~ Ernie Barnes, “Pads to Palette” (p. 76)

His football career led to Barnes’ first art exhibition. The Bronco Backers Club asked Barnes to display his work at a Club party. When a man asked how much Barnes wanted for his painting “The Bench,” Barnes threw out the number $25,000, not wanting to part with the painting. The man wrote a check and handed it to Barnes. Barnes then refused to take it. The bartering drew a small crowd, and in that crowd was a reporter from Sports Illustrated Magazine. The reporter wrote about it and published a photo of “The Bench,” thus catapulting Barnes, as a football player-artist, into the national spotlight. In addition, the Denver Post ran a four-page article on Barnes’ work, garnering him the attention that allowed Barnes to supplement his football income with the sale of clown paintings on cork panel. As he continued to search for emotional truths in his sport paintings, Barnes “began distorting and elongating the proportions, trying to relate what it felt like within the context of a certain movement,” resulting in the characteristic elongation and disproportionate space in what came to be known as Neo-Mannerism.

After joining the Saskatchewan Roughriders football team in Canada, Barnes fractured his ankle. He ended his active football career at the age of 26, but the experiences remained a lifelong part of his artistic inspiration. Barnes borrowed money from friends and pawned two prized patches and a ring in order to move himself and his then pregnant second wife, Janet, into a dilapidated Hollywood motel. There, Barnes walked six miles to the Hilton Hotel Corporation in Beverly Hills to propose to hotelier Barron Hilton that Barnes be made the Official Artist for the American Football League (AFL). Hilton loved the idea, encouraged Barnes to make the proposal to team owners, and commissioned Barnes at $1,000 to paint a portrait of Lance Alworth. The owner of the New York Jets, Sonny Werblin, invited Barnes to New York. Werblin had three art critics assess Barnes’ work, then offered Barnes $14,500—$1,000 more than he made in his last season of football—to paint 30 paintings over the next six months. Ernie Barnes, the artist, was launched.