John Robinson – “Sports Beauty in Bronze” – 1988 Sport Artist of the Year

Artist Biography | Style & Inspiration | Key Sport Works & World Influence

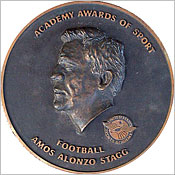

Stagg Medallion

Bronze has been used by great civilizations of the world for both art and weapons. John Robinson, 1988 Sport Artist of the Year, preferred the former. In Robinson’s hands, bronze became artillery for inspiring contemplation and searching out the meanings of symbols and mathematics. With his sculptures he explored the unique and spiritual human experience through creation of natural forms, celebrating the wonder of life not just in bronze, but wood, stainless steel, marble, and tapestries as well. Though the reach of Robinson’s sculptures and their meanings extends worldwide, the inspiration and the necessity to create came from within him. As he wrote in his three volume autobiography, the story of John Robinson “is the story of someone passionate about using his hands as his imagination dictates…”(Robinson, 2005).

Bonds of Friendship

Born on 4 May 1935 in the United Kingdom, John Robinson and his brother Michael were sent to Australia at the strong suggestion of his grandfather to protect them from the escalation of World War II in Europe. There, Robinson attended grammar school in Melbourne. Far from the devastation of the war, the landscape of Australia ingrained itself in Robinson’s very being.

After the war, Robinson returned to England where he attended Rugby School, one of the UK’s leading boarding schools. Looking back, Robinson’s fondest memory of Rugby School was its art school. There, his art teacher, Fabio Barraclough, invited Robinson to join a sculpting group that met in a small studio under the stairs. Carving wood was Robinson’s first “hands on” experience with art. Robinson’s first sculpture was a “hula hula girl,” a subject that he says he chose in reaction to the atmosphere of his all-boys prep school. His brief experience with art at Rugby School was the only formal teaching of art he ever had.

“Learning to carve the wood was a fabulous experience and remains the happiest memory of all my days at school.” ~ John Robinson, From the Beginning Onwards

Later Robinson joined the Merchant Navy as a deckhand on a cargo ship. As part of the Merchant Navy he returned to Australia and felt as if he had come home. He decided to make farming in Australia his career. He attended Roseworthy Agriculture College in South Australia, worked as a jackaroo (farm apprentice) and for five years traveled the Outback working periodically at sheep and cattle stations. With a loan from his father, Robinson bought a stretch of land in the Ninety Mile Desert of South Australia and built a home and sheep farm. He was soon married and worked as his sheep farm and family grew. The stark beauty of the Australian landscape, provided all the art instruction Robinson required.

“John is entirely self taught, but his art is generated by his life as part of the wide world, with experience of exploring Western Australia, working his own sheep farm and bringing up a family.” ~ Ronnie Brown, “John Robinson, Sculptor,” Hyperseeing, 2007

Robinson’s mother sent the “hula hula” girl he had carved while at Rugby School to his home in Australia. He placed it on a bookshelf in his sitting room. The “hula hula” girl was a constant reminder of the pleasure he got from sculpting, and acted as the inspiration to return to the pastime. He bought modeling clay and began sculpting first his children, then his friends’ children. What started as a hobby grew into a calling. Robinson considered returning to the UK to pursue his art when his mother sent yet another influential artifact that solidified his decision. It was a note that read:

“Do you remember my giving you a set of woodcarving chisels when you were twelve? It was because a fortune-teller had told me that my youngest son would be a sculptor.” ~ From the Beginning Onwards

Robinson sold his farm for enough for his family to live in the UK for two years. There he met with Enzo Plazzotta, a British sculptor. Robinson showed Plazzotta some of his work and asked if he should pursue earning a living as a sculptor. In return Plazzotta asked “Do you want to do anything else other than be a sculptor?” Robinson said no. Plazzotta replied, “Then why are you asking me? Go and do it.”

At the time, Robinson mostly sculpted children and other representational subjects. His art was mainly displayed at Harrods Fine Arts Gallery. In the mid-1970s, when he began experimenting with more symbolic work, the Gallery turned him away. Having inherited his mother’s flat in London, Robinson traded it for a site for his own gallery in London and named it Freeland, after his mother’s maiden name. With that investment, Robinson was too far into sculpting as a way of life to turn back.

“I was not at all sure what I was going to do with these sculptures … but I was being carried along on the crest of a wave and just forged ahead and, in hindsight, must have been completely mad.” ~ John Robinson, From the Beginning Onward

Opening the Freeland Gallery introduced Robinson to his three greatest patrons: Damon de Laszlo, Robert A Hefner III, and Professor Ronnie Brown. Collectively, the patrons donated Symbolic Sculptures to institutions such as the Aspen Centre for Physics, Aspen Institute, Field Institute Toronto, Cambridge Institute of Astronomy, Universities of Macquarie Sydney, Wales Bangor, Harvard, Montana State, Durham, Oxford and Cambridge’s Isaac Newton Institute.

image sources

- Robinson-feature: John Robinson