Armand Arman – “THE ORACLE OF ENVIRONMENTAL ART” – 2003 SPORT ARTIST OF THE YEAR

Artist Biography | Style & Inspiration | Key Sport Works & World Influence

“It’s the response that you get from seeing all those objects together, the shape, the size, the colour… that is most important to me. The first goal is the visual experience. I’m not into conceptual art simply for the sake of the concept.” ~ Arman, Accumulation in Relation, Mayor Gallery, London, 1997; p.2

4th of July

Using piles of debris and found objects to make sculpture is part of a style of Found Art dubbed, “Accumulation Art.” Some Found Art uses only one item or uses parts of several items to form an image. Accumulation Art is about quantity, about seeing what new perceptions come from grouping overwhelming numbers of the same object. An object’s transformation from familiar to new begins when so many objects are grouped together that a person cannot count them and it reaches its abstract zenith when the number of objects is so great that they blend in the viewer’s visual perception into an unfamiliar, unrecognizable mass — a new creation. In a 1965 Paris interview in L’Oeil magazine with Alain Jouffroy, Arman explains this process:

“There are thresholds that I am very conscious of. At the first threshold, there must be a grouping of objects which contains an unidentifiable number. Five objects constitute a visual message, and eighty-eight fingers become an indecipherable mass. At the second threshold, the accumulation limit changes the object’s identity without modifying its emotional meaning: sixty violins can be recognized, but blend into a mass. The third threshold is when the object loses all its identity.”

Race in the Mud

Arman uses this anonymity achieved by object overload to create a new “thing” imbued with new meaning of his intent. He distinguishes his style from those of other schools of modern art working with familiar found objects. Arman’s interest is in the variety of roles that an object takes as it changes settings and quantities. In the catalogue for his 1989 exhibition at Mayor Gallery, London, Arman’s comment summarizes the conceptual history of Neo-Realism and his place in it:

“As I evolved into object art, I found myself being called a Pop-Artist. But the term isn’t exactly right. Pop-Artists redo the object. I use the real object. Marcel Duchamp, who is the obvious father of object art, might have taken a soup can and put it on a red pedestal. (Andy) Warhol would repaint the soup can. (Jasper) Johns would cast it in bronze. I’d take the soup can and cut it into pieces or weld hundreds of them together in order to change the state of the object from what it was when you first saw it in the supermarket. My interest is in exploring the various worlds of the object.”

Untitled

Marcel Duchamp and the rebellious Dada movement of the 1920s exerted a strong influence on Arman’s early work. Arman was attracted to Dada’s iconoclastic urge to break up the old order and present radical new ideas that would shock bourgeois society. However, the negativity and Nihilism of Dada did not fit Arman’s optimistic world view. He believed that there was hope for humanity in spite of the enormous problems and he wanted his art to express this.

Marcel Duchamp, one of Dada’s most illustrious members, created several original works that would stand as turning points in art history and key foundation blocks of both Surrealism and Pop Art. In 1914, Duchamp took a bottle rack from a Paris hotel and exhibited it as art. The first “readymade” sculpture, Duchamp’s work is a clear inspiration for Arman’s presentations of found objects. Duchamp also was obsessed with machines. He painted, sculpted, and assembled them into radically inventive art forms. Duchamp discovered the primitive inside the industrial as he mounted a bicycle wheel on a kitchen stool and ceramic wall fixtures on pedestals that at quick glance look a great deal like figures of African or Aboriginal idols.

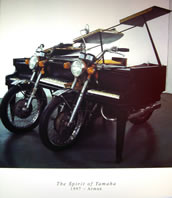

The Spirit of Yamaha

In homage to the New Realists’ debt to Dada artist Marcel Duchamp, Arman’s friend, Pierre Restany titled his second manifesto, “Forty Degrees above Dada.” Restany sees Duchamp’s use of readymade objects in art as a symbol of a shift into the modern world of the common man in urban life. He takes readymade objects not as signs of depressing mass production but as energizing symbols of immersion in the industrial world, coming out the other side into a liberated modern sensibility. He says, “The readymade is no longer the height of negativity but the basis of a new expressive vocabulary.” It is at this optimistic point that Arman comes to his use of readymade industrial objects and then pushes the technique into new territory, including explorations of movement and sports themes.

Arman’s sculptures made of sliced parts of musical instruments show his admiration for their remarkable construction as well as his fascination with rhythm and isolating an object’s essential elements. Arman’s piano and cello sculptures explore questions about the core of the instruments’ power and the effect of quantity on power. One cello is often presented in Arman’s early works. In later works, he piles on more and more objects until the fused mass surprises our stereotypes and makes a new statement.

Lucky

Across the sea in the United States, Pop Art was born out of rebellion against Abstract Expressionism. In Europe, Pop Art’s counterpart, New Realist Art was a rebellion against the theories of the Dada movement. Pierre Restany’s second manifesto states that, “The New Realists consider the world as a picture, the great fundamental masterpiece from which they take fragments endowed with universal significance.” Arman’s fragment accumulation artworks exerted a significant influence on American Pop Art explorations of modern ways to look at familiar objects and express movement. Arman bridged these two art worlds as he moved from continental Europe to New York, importing his extraordinary athletic aesthetic with him. The United States Sports Academy is privileged to have an installation of Arman’s titled “Lucky” in its sculpture garden. The powerful steel sculpture is a pyramid-shaped stack of steel helical bits used in drilling for oil. This is a fitting monument on the campus as it recognizes the Academy’s major sport programs in many oil rich countries starting with the Kingdom of Bahrain, which provided the financial base for the Academy to become the largest graduate school of sport in the world.

image sources

- Arman-feature: Armand Arman